Sea turtles are highly migratory, roaming between foraging and nesting grounds, and seasonally to warmer waters, often travelling between hundreds to thousands of kilometres. An adult female Leatherback was tracked using satellite telemetry travelling more than 19,000 kilometres from Indonesia to Oregon, one of the longest migrations of any vertebrate animal ever recorded. Loggerheads born in Japan migrate approximately 12,000 kilometres to Baja California, Mexico to feed and mature. Once they reach sexual maturity, they migrate back to Japan to breed and nest. While all sea turtles are migratory, orientation and navigation have been thoroughly studied in the Loggerhead and Green sea turtle species. Overall, most research of sea turtles have been done on nesting beaches as they are easily accessible but much has yet to be learnt of sea turtles in their aquatic habitat where they spend over 90% of their lives.

Hatchlings

Migration starts from the moment a hatchling emerges. Eggs hatch at night when it is cooler and safer from predators. As soon as hatchlings leave their eggs, they rapidly make their way towards the ocean guided by the low bright lights of the moon and night sky reflecting off the water. As a result of coastal development however, artificial lights have misguided hatchlings away from the sea in recent decades, often resulting in the death of the hatchlings from dessication, predation and oncoming traffic before they can find their way back to the ocean. Though recent conservation efforts have reduced levels of artificial lighting along nesting beaches and the incidence of misoriented hatchlings have declined.

Aside from the position of light, sea turtles are also guided in the direction of the water by the gentle downward slope of the beach and the auditory cue from the waves breaking, thus leading hatchlings towards the sea.

It is believed that sea turtles establish a geomagnetic imprint of the magnetic features of the beach where they were born (either during the offshore migration or even while still in the nest) which is engrained in their ‘internal magnetic compass’ for life so that they return to the same beach during each breeding season once they reach adulthood and sexual maturity.

Within the first two or three days after emergence, nourished by their yolk sacs and thus do not feed, hatchlings start their migration on a ‘swimming frenzy’ into deeper waters where they are less vulnerable to predators. Upon entering the water, hatchlings are initially guided by the direction of the waves and are naturally inclined to swim against them. This instinct guides hatchlings towards the relative safer open ocean. Various anecdotal observations indicate that hatchlings cease swimming into waves after several hours in the ocean suggesting that waves are used as an orientation cue only for a short time after entering the sea. This would make sense as once hatchlings pass the narrow wave refraction zone (where waves proceed directly to the shore), waves are no longer a reliable orientation cue. From here on, it is likely that turtles rely on their internal magnetic compass though their directional preference may have influence from environmental factors such as position of light or direction of waves. For example, sea turtles on Florida’s West Coast might acquire a directional preference for west after swimming west into the waves and therefore set their magnetic compass for west and then swim in that direction until reaching the Gulf Stream Current.

On the other hand, because hatchlings have had no prior experience in the ocean, some studies suggest that turtles emerge from the nest already programmed to respond to certain magnetic fields by swimming in certain directions. This would have interesting implications for conservation efforts. For example, it may be problematic to replenish an endangered group of Loggerheads from one ocean basin with Loggerheads from another ocean basin as the latter group of Loggerheads may have different inherited migratory and navigational responses. Current difficulties to reestablish a group of endangered nesting Green Sea Turtles in Bermuda with eggs from Costa Rica maybe due to this.

The ‘Lost’ Years

Once hatchlings enter the sea, they are rarely seen for 1-3 years. These are known as the ‘lost’ years. Scientists believe that hatchlings spend the first few years of their lives in the pelagic deeper waters riding prevailing surface currents, situating themselves within floating seaweed where they can find food and stay protected from coastal predators. Many hatchlings from the Atlantic and Caribbean make their way into Gulf Stream currents, which are filled with floating sargassum (brown seaweed with berry-like air bladders). However, individuals may not necessarily take the same migratory route.

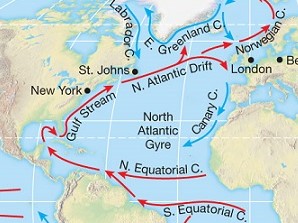

It has been demonstrated that sea turtles can detect both the geomagnetic inclination angle (isoclinics) and intensity (isodynamics) which then form a sort of magnetic map that may provide turtles with a position-fixing system and help them navigate towards their target. Isoclinics and isodynamics have also been observed to aid hatchlings and juveniles stay within ocean currents during their early years. For example, young Loggerheads from Florida spend several years in the North Atlantic Gyre (Figure 1) where conditions are favourable for survival and growth. However, at the northern edge of the gyre, the current divides; the northern branch continues to the United Kingdom where the water temperature rapidly decreases. Loggerheads swept into this current soon die from the cold. Similarly, Loggerheads that venture south of the gyre risk being swept into the South Atlantic current system, away from their normal range. However, their ability to detect latitudinal extremes through isoclinics and isodynamics aid them in keeping within the boundaries of the gyre.

Due to the much shorter migratory distances and smaller geographic range of Flatback Sea Turtles, research suggests that Flatback hatchlings do not go through an oceanic phase, but rather remain closer to coastal waters within 15 kilometres of land.

After these initial few years, juvenile sea turtles move closer to nearshore habitats where they spend their days foraging for food and growing until they reach adulthood and sexual maturity. This is when they migrate to new feeding ground where they spend the rest of their lives, except during breeding season. Contrary to nesting beaches where sea turtles return to breed innately even if these specific locations have been lost to dredging and other human activities, the selection of feeding sites is unlikely to be genetically programmed, but rather based on environmental conditions such as food abundance and availability of shelter. The magnetic features of these favoured sites are then remembered so that sea turtles can return to them from long distances.

Breeding and Nesting

During breeding season, both males and females migrate from their primary feeding grounds to the waters near nesting beaches to mate. While sea turtles usually return to the same beaches where they were born, scientists studying Loggerheads have discovered that turtles that nest on beaches with similar magnetic fields are genetically similar to one another. This means that sea turtles migrate back to their natal beach or beaches with similar magnetic fields to that of their natal beach, even if that beach is geographically distant or with different environmental traits from the beach they were born.

Many of the major nesting beaches are located on continental shorelines aligning approximately north to south where the isoclinics and isodynamics also vary from north to south. While an entire stretch of shoreline may be available, sea turtles are able to swim along these shorelines until they reach a specific location to nest as a result of their geomagnetic imprinting and magnetic navigation. The same impressive ability is used by sea turtles that nest on islands. For example, a population of Green Sea Turtles nest on the 8 kilometre-long island of Ascension 2,000 kilometres off the Brazilian coast and are able to reach the island each breeding season with pinpoint accuracy. It is likely that they use a combination of long-range and short-range cues to find these exact locations, with long-range cues being geomagnetic features and short-range being local cues such as auditory, visual, olfactory or other local cues to find an appropriate nesting site. In sea turtles, short-range cues have not been extensiely studied.

Furthermore, magnetic fields change slightly every year in a phenomenon called the magnetic drift, and since sea turtles can take 10-30 years to reach maturity, the magnetic field in their natal beaches may change by the time they return to breed, thus shifting the location of their geomagnetic imprint to several kilometres away. This further supports the likely utilisation of short-range cues to find precise nesting sites once nesting turtles arrive in the general geomagnetic region.

Research has suggested a short-range navigational role of wind-borne information on sea turtles, possibly by creating a sort of plume. The nature of the wind-borne cues used by sea turtles is currently unknown though chemical cues and/or sounds carried by the wind is likely.

These findings strongly suggest that geomagnetic imprinting and magnetic navigation help shape the population structure of sea turtles. This also has important implications for the conservation efforts of sea turtles where conservation groups should consider the beach’s magnetic field as sea walls, power lines and large beachfront developments may alter the magnetic field of that beach.

Earth’s Magnetic Field

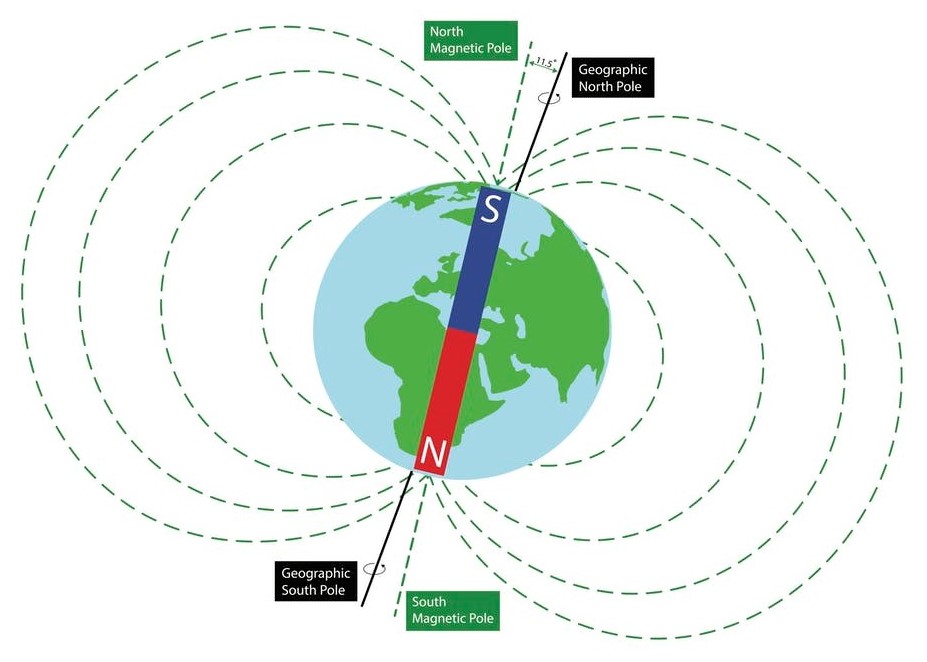

Earth’s Magnetic Field resembles a N-S bar magnet where field lines emerge from the southern half of Earth and re-enter in the northern half (Figure 2).

Inclination Angle (Isoclinic): This is the angle in which the magnetic field lines intersect the surface of Earth. This varies with latitude and therefore sea turtles are able to determine their latitudinal positions by detecting this feature. The angle ranges from 0° at the magnetic equator to 90° at the magnetic poles.

Intensity (Isodynamic): This is the strength of the field. While the variation is less predictable than the inclination angle, the general trend is that the intensity is strongest at the magnetic poles and weakest at the magnetic equator, also providing latitudinal information. Detecting both the inclination angle and intensity might provide sea turtles with information about longitude as well, because, while both inclination and intensity vary with latitude, they do so independently. Thus, most locations within an ocean basin have unique combinations of intensity and inclination.

References

Brothers, J. R. & Lohmann, K. J. Evidence that Magnetic Navigation and Geomagnetic Imprinting Shape Spatial Genetic Variation in Sea Turtles. Current Biology 28, 1325-1329 (2018).

Hays, G. C. Ocean Currents and Marine Life. Current Biology 27(11), R470-R473 (2017).

Islameta Group: Sea Turtle Navigation

Lohmann, C. M. F. & Lohmann, K. J. Sea Turtles: Navigation and Orientation in Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior (ed. Breed, M. D.). 101-107 (Elsevier Science, 2010).

Lohmann, K. J., Lohmann, C. M. F., Ehrhart, L. M. et al. Geomagnetic Map Used in Sea-Turtle Navigation. Nature 428, 909-910 (2004).

Luschi, P., Hays, G. C. & Papi, F. A Review of Long-Distance Movements by Marine Turtles, and the Possible Role of Ocean Currents. Oikos 103(2), 293-302 (2003).

Science: Sea Turtles Ride the Waves

Sea Turtle Conservancy: General Behaviour

See Turtles: Sea Turtle Migration

Image Source: Figure 1. North Atlantic Gyre – Offshore Engineering, 2022

Image Source: Figure 2. Earth’s Magnetic Field – Technologies in Industry, 2022