Human activities which release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, such as the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation, are the primary contributors to rapid warming. Greenhouse gases blanket the Earth’s atmosphere trapping heat and causing the planet to heat up. Forests are important carbon sinks that absorb carbon, but when forests are cleared, not only are they unable to absorb carbon, they also release carbon and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, thus exacerbating warming. As the planet’s greatest carbon sink, approximately a third of all human-related greenhouse gas emissions are absorbed by the oceans, including the excess heat and energy released from rising greenhouse gas emissions trapped in the Earth’s system. Climate change has a strong impact on both the on-shore and off-shore lives of sea turtles through the effects of sea level rise, ocean acidification, severe weather, temperature changes affecting the temperature of nesting sands, and changes in ocean currents.

Sea Level Rise

Melting polar caps, ice sheets and glaciers, and thermal expansion of the oceans, as a result of climate change is causing oceans to warm and sea levels to rise which causes beaches, ecologically productive wetlands and sand barriers to disappear. The disappearance of beaches is a threat to sea turtle reproduction as during nesting season, sea turtles migrate hundreds or even thousands of kilometres from their primary feeding grounds to their natal beach (or beaches with similar magnetic fields to that of their natal beach) (see Migration: Orientation & Navigation). If these beaches disappear, sea turtles may not find another suitable beach to nest or resort to nesting in less than ideal conditions, which lowers the chances of nesting success. Over the past 40 years, sea level has risen at an average of 2 millimetres each year. Sea level rise projections for the end of the 21st Century range from 0.18 to 0.59 metres. Even a small rise in sea level could result in a large loss of beach nesting habitat. In the US, the beaches of Florida, where 90% sea turtle nesting takes place, is one of the most vulnerable land areas to sea level rise alongside Lousiana and Chesapeake Bay.

Ocean Acidification

Ocean acidification is caused by the increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which is absorbed by the ocean. In the ocean, carbon dioxide reacts with seawater to form carbonic acid, which causes the acidity of seawater to increase. Sea water has a pH of 7.8 to 8.5, which is alkaline, but as the ocean continues to absorb more carbon dioxide, the pH decreases and the ocean becomes more acidic. Thus far, the pH of the oceans has decreased on average by 0.1, which represents a 30% increase in acidity. Each year, the oceans absorb an additional two billion metric tonnes of carbon.

The pH scale ranges from 0 to 14, with 7 being neutral. A pH below 7 is acidic and a pH greater than 7 is alkaline (or basic). The pH scale is logarithmic, meaning that an increase or decrease of an integer value changes the concentration by a tenfold. For example, a pH of 3 is ten times more acidic than a pH of 4. And a pH of 3 is a hundred times more acidic than a pH of 5.

Ocean acidification can negatively affect marine life, causing organisms’ shells and skeletons made from calcium carbonate to dissolve, such as corals, sea urchins, sea snails, oysters and foraminifera. The more acidic the ocean, the faster the shells dissolve. While this excludes sea turtles (as their shells are composed of keratin), animals that produce calcium carbonate structures store carbon in their bodies. By dissolving their shells and skeletons, ocean acidification could negatively affect this natural way of cutting carbon from the atmosphere. In addition, organisms end up using more energy to repair or thicken their shells, consequently reducing the animals’ abilities to grow and reproduce, which may lead to reduced food availability for other creatures and threatening ecosystems. Furthermore, dissolving corals reefs will remove an important food source for sea turtles, particularly Hawksbills, putting them at risk of starvation.

Acidification also decreases the availability of key nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphates, silica and iron, and in turn reduces the growth of plankton, which are important carbon dioxide absorbers. Green Sea Turtles are at high risk due to their restricted diet primarily consisting of sea grasses and algae, which rely on the presence of these vital nutrients. Loggerheads have a more generalised diet, which provides some resilience to this threat.

Acid rain can leach copper, aluminium, mercury and other heavy metals out of the soil and into the ocean, which can cause eutrophication, deformities and internal injuries (see Chemical Pollution).

Severe, Frequent & Unpredictable Weather

While hurricanes and cyclones are a natural part of the Earth system which sea turtles have withstood for over 110 million years, more severe, frequent and unpredictable storms caused by climate change could dramatically increase beach erosion rates, thus endangering sea turtle nesting habitats through washing away entire beaches, reducing the quality or area of a nesting beach, exposing eggs, flooding nests and limiting oxygen to the eggs resulting in drowning of developing embryos, or completely washing nests away. Increase in severe weather can also lead to an increase in plastic pollution as plastic debris can be blown out to sea where sea turtles and other marine creatures mistake the debris for food, or washed ashore causing additional obstacles for hatchlings trying to reach the sea or for females trying to come ashore to nest (see Plastic Pollution).

Severe storms can also cause habitat loss in the ocean. During the first few years, hatchlings situate themselves within floating sargassum (brown seaweed with berry-like air bladders) where they find food and stay protected from coastal predators. If a hurricane or cyclone travels through this area, it can destroy this habitat exposing hatchlings to predators or washing them back to shore along with the sargassum beds. These post-hatchlings are commonly called washbacks. Washbacks are typically fatigued from trying to fight the strong tides, and they often require trained and authorised personnel to rescue them from the beach and bring them to a rehabilitation facility where they can regain their strength. In addition, severe storms can increase sedimentation and run-off from coastal flooding, and decrease visibility and light penetration.

Warming Temperatures

Temperature rise threatens sea turtles at all stages in their life cycle. The temperature inside the nest determines the sex of the hatchlings. A temperature of approximately 29.5°C produces a mix of male and female hatchlings, while higher temperatures produce females and cooler temperatures produce males. Higher temperatures as a result of climate change cause the sand to heat up and lead to a higher proportion of female hatchlings, creating a significant threat to sea turtle reproduction and genetic diversity. A 2018 study by Jensen and colleagues found that females accounted for 99.1% of juvenile Green Sea Turtles originating from nesting beaches in the north of the Great Barrier Reef while turtles originating from the cooler southern Great Barrier Reef nesting beaches still exhibited a female bias of 65-69%. Additionally, when the sand is too hot (~34°C), it can lead to hatchling mutations or complete nest failure. Dry sand can increase unsuccessful nesting attempts, cause nest chambers to collapse while being excavated, and dehydrate and destroy nests. A study on Loggerhead Sea Turtles in the Mediterranean had previously found that in extreme cases, turtles laid eggs about 18 days earlier when waters warmed by 1°C.

Warmer ocean temperatures also negatively impact food sources for sea turtles and other marine organisms by affecting the distribution, quality and abundance of prey species, thus threatening ecosystems and putting sea turtles and other marine life at risk of starvation. Warmer waters also reduce the movement of nutrients from the cooler ocean depths to the surface in a process known as upwelling. Fewer nutrients in surface waters result in species mortality and diminished reproduction. Some marine organisms would require higher metabolic rates to survive in warmer temperatures with lower oxygen levels (oxygen dissolves more efficiently in cooler temperatures – seawater saturated with oxygen has 35% less oxygen at 30°C than at 8°C), resulting in their stunted growth, reduced reproduction and lower food availability for sea turtles and other creatures. The lowered availability of food could reduce the turtles’ resilience and push them to more productive areas, if they exist. Sea grasses on which Green Sea Turtles depend on will also become less productive as a result of warmer water. Additionally, sea turtles are ectothermic (their body temperature depends on the external environment) which means individual metabolic rates may increase with warmer water temperatures in foraging grounds, thus requiring more food supply to support them. Hawksbills in the Persian Gulf have been observed to migrate away when coastal waters reached around 32°C, to deeper, cooler waters where they stayed until temperatures near the coast dropped again. This type of response to rising ocean temperatures is likely similar in other turtle species. This, however, may potentially result in increased exposure to threats and/or reduced food availability.

Coral reefs, which are an important food source for sea turtles, particularly Hawksbills, are in great danger. Corals exist within a very narrow temperature range. As a result of rising temperatures, coral reefs are suffering from bleaching, which kills off parts of the reef. Corals are usually covered in zooxanthellae. These tiny creatures absorb light and use photosynthesis to create food for the coral. When corals become stressed due to increased water temperatures or pollution, they can stimulate dormant viral infections in the zooxanthellae. Increased temperatures and chemical pollution cause viruses within the zooxanthellae to replicate until their algal hosts exploded, spilling viruses into the surrounding seawater, which could potentially spread infection to nearby coral communities. Without the zooxanthellae, they lose their main food and oxygen source and the wide array of colours that make corals so attractive, exposing the protective skeletons of the corals. Almost half of coral reef ecosystems in the US are in poor or fair condition. Since 2005, the Caribbean region has lost 50% of its corals, largely because of rising sea temperatures. From 1997 to 1998 alone, mass bleaching is estimated to have killed 16% of the world’s coral reefs. While strong signs of recovery have been observed in some locations, many will take decades to fully recover, often with human intervention.

Changes in Ocean Currents

The ocean has an interconnected current system powered by the wind, tides, Coriolis effect, solar energy, topography of nearby landmasses and ocean basins, and water density differences. Density differences in ocean water contribute to a global-scale circulation system, also known as the global conveyor belt. The global conveyor belt includes both surface and deep ocean currents that circulate the globe in a 1,000-year cycle. Surface ocean waters absorb heat from the atmosphere which is then circulated around the planet by ocean currents. Heat causes matter to expand making it less dense (and lighter) than cold matter. In terms of oceanic circulation, denser cold water near the Poles sink deeper into the ocean and move closer to the Equator while warmer waters at the Equator move closer toward the Poles where it cools and sinks, and thus the cycle continues. As a result of rising temperatures, waters at the Poles would become less cold and less dense, therefore less likely to sink. Ocean water density is also influenced by its salinity. Melting polar caps, ice sheets and glaciers would decrease the salinity of the ocean, making the water less dense and less likely to sink. Without sinking cold water, ocean currents could slow down, ultimately stop in some regions, or lead to changes in ocean currents horizontally, vertically, at the surface and in the deep sea. These types of currents can differ in scale, speed and energy, but remain interconnected.

Sea turtles, particularly hatchlings, rely on ocean currents for migration. With changes in ocean circulation, sea turtles may have to alter their migration patterns and shift their range and nesting timings. Similar to changes in ocean temperatures, changes in ocean circulation impact the distribution and abundance of food sources, thus threatening ecosystems and putting sea turtles and other marine life at risk of starvation. Shifting ocean currents may also introduce new predators that could harm sea turtle populations.

As the movement of heat energy through local and global ocean currents can affect the regulation of local weather conditions and temperature extremes, current disruption can lead to more severe weather. For example, the climate in Europe is typically mild due to the heat brought by an ocean current in the Gulf of Mexico. However, melting ice is weakening this current, thus projecting more severe weather as a result of climate change.

Summary

- Human activities which release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, such as the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation, are the primary contributors to rapid warming.

- Climate change has a strong impact on sea turtles through the effects of sea level rise, ocean acidification, severe weather, temperature changes affecting the temperature of nesting sands, and changes in ocean currents.

- The disappearance of beaches as a result of melting polar caps, ice sheets and glaciers is a threat to sea turtle reproduction as sea turtles may not find another suitable beach to nest or resort to nesting in less than ideal conditions.

- Ocean acidification causes organisms’ shells and skeletons made from calcium carbonate to dissolve. Animals that produce calcium carbonate structures store carbon in their bodies. By dissolving their shells and skeletons, ocean acidification could negatively affect this natural way of cutting carbon from the atmosphere.

- Organisms end up using more energy to repair or thicken their shells, consequently reducing the animals’ abilities to grow and reproduce, which may lead to reduced food availability, threatening ecosystems and organisms.

- Dissolving corals reefs will remove an important food source for sea turtles, particularly Hawksbills, putting them at risk of starvation.

- Ocean acidification causes organisms with shells and skeletons made of calcium carbonate to dissolve, such as corals, sea urchins, sea snails, oysters and foraminifera. These structures store carbon. With their dissolving structures, this reduces their ability to capture carbon from the atmosphere. They also require more energy to repair their shells which stunts their growth and reduces their ability to reproduce, which may lead to reduced food available for other creatures.

- Acidification decreases the availability of key nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphates, silica and iron, and in turn reduces the growth of plankton, sea grasses and algae, potentially putting sea turtles at risk of starvation.

- Acid rain can leach copper, aluminium, mercury and other heavy metals out of the soil and into the ocean, which can cause eutrophication, deformities and internal injuries (see Chemical Pollution).

- More severe, frequent and unpredictable storms caused by climate change could dramatically increase beach erosion rates, thus endangering sea turtle nesting habitats.

- Increase in severe weather can also lead to an increase in plastic pollution.

- Severe storms can destroy the sargassum habitats young sea turtles use for food and shelter, or even wash the young turtles back ashore, known as washbacks, which are often fatigued from trying to fight the strong tides.

- Higher temperatures as a result of climate change cause the sand to heat up and lead to a higher proportion of female hatchlings, creating a significant threat to sea turtle reproduction and genetic diversity.

- When the sand is too hot (~34°C), it can lead to hatchling mutations or complete nest failure.

- Dry sand can increase unsuccessful nesting attempts, cause nest chambers to collapse while being excavated, and dehydrate and destroy nests.

- Warmer ocean temperatures negatively impact food sources by affecting the distribution, quality and abundance of prey species, thus threatening ecosystems and putting sea turtles and other marine life at risk of starvation.

- Sea turtles are ectothermic which means individual metabolic rates may increase with warmer water temperatures in foraging grounds, thus requiring more food supply to support them.

- As a result of rising temperatures, coral reefs, an important food source for sea turtles, particularly Hawksbills, are suffering from bleaching.

- With changes in ocean currents caused by rising temperatures and reduced salinity, sea turtles may shift their range, migration patterns and nesting timings. Changing currents can affect the abundance of food for sea turtles and potentially introduce new predators that could harm sea turtle populations.

History & Future of Climate Change and Sea Turtles

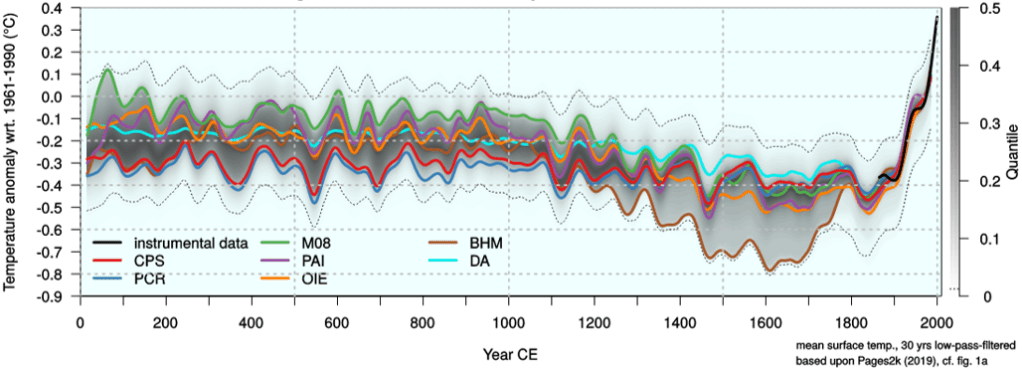

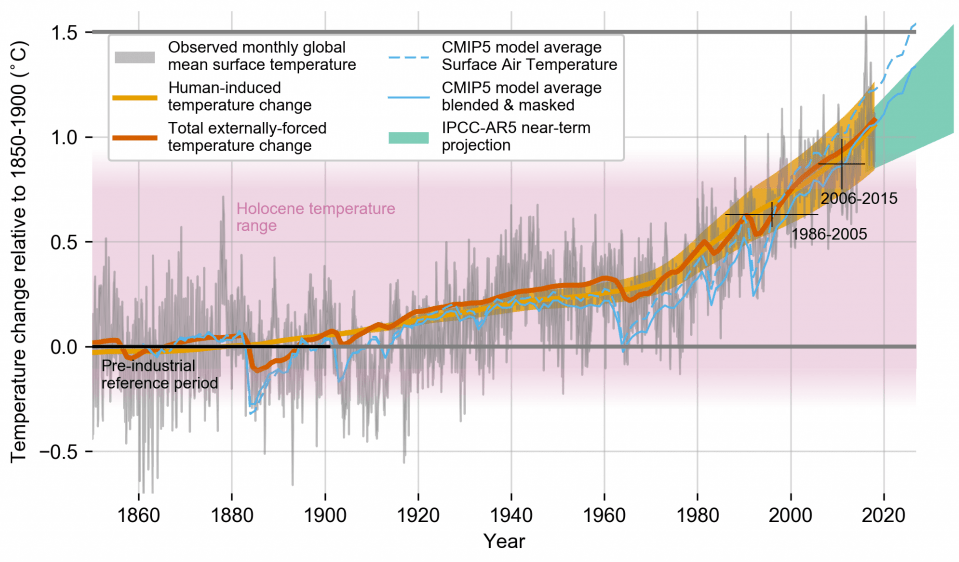

While changing climates have always been a part of Earth’s cycle throughout Earth’s 4.5 billion-year history, global surface temperatures have gradually increased since the start of agricultural practices around 10,000 years ago, and dramatically since the Industrial Revolution. Figure 1 shows the global temperature change over the last 2000 years. During 800-1200 AD, there was a period known as the Medieval Warm Period, and from the early 14th Century to the mid-19th Century, temperatures dropped to what is known as the Little Ice Age. However, both these periods were not global events, unlike today’s drastic increase in temperatures which is affecting the entire planet, shown in Figure 2 and benchmarked against pre-Industrial references. Since 1880, Earth’s average surface temperature has risen by 0.07°C every decade, with the rate of temperature change accelerating in recent decades and more than doubling to 0.18°C since 1981. Since the Industrial Revolution, technological advancements came at the cost of burning fossil fuels – releasing significant amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, in addition to clearing land for agriculture and developments through deforestation. In recent decades, globalisation and trade progressed more than ever before, and global population growth peaked at 2.1% per year between 1965 and 1970. Industrialisation patterns intensified to meet the demands of an expanding global population with increasing consumption habits, and the advancement of the modern world, despite the devastating impacts this was having on the environment.

Evident in their resilience, sea turtles are highly adaptable and may respond to projected climatic changes by shifting their nesting range to climatically suitable areas (which may result in either increased exposure to threats or fewer). While sea turtles have survived climate change events over the last 150 million years, today sea turtles are struggling to survive not only due to the rapid warming of global surface temperatures, but simultaneously battling numerous other human-caused threats. In addition, previous climate events didn’t occur as rapidly and were regional in scale, unlike today’s global phenomenon. Sea turtle populations have drastically declined, and unless humans hold an immediate intervention, we will soon see the extinction of these beautiful creatures that have roamed Earth for 150 million years, along with many other precious species.

A 2020 study by Fuentes and colleagues predicted future climatically suitable nesting areas for sea turtles. While nesting ranges of sea turtles are not predicted to change between current and future climatic projections (except for the northern nesting boundaries of Loggerheads), climatically suitable nesting grounds are predicted to decline with Loggerheads experiencing the highest decreases (10%) followed by Greens (7%) and Leatherbacks (1%). In addition, sea level rise is projected to submerge about 80% of nesting habitats predicted to be climatically suitable in the future. However, not all hope is lost as with rising sea levels new beaches will be created. A 0.5 metre sea level rise (a conservative estimate) is predicted to result in a net habitat gain, especially for Leatherbacks.

Solution

The first and foremost solution to mitigate climate change is to cease our reliance on fossil fuels through switching to renewable forms of energy, which will end the unnatural release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The increase in renewable energy also leads to the creation of jobs in energy conservation and renewables which will help swiftly shift the economy to more circular and cleaner, and away from fossil fuels.

Fossil fuels are finite and we will run out of it eventually. Humans can live without fossil fuels, especially now that renewable alternatives are available. We survived without it in the past. We have become so reliant on materials and convenience that we have forgotten what life was like when less was more. A combination of renewable energy forms as well as reduced consumption and increased awareness of our energy footprint through all forms of consumption means that the use of fossil fuels can cease imminently. Relearning to enjoy the simple things in life without constant connection to all things digital will also reduce our reliance on fossil fuels and other forms of energy. Our life satisfaction and happiness will also greatly increase.

In addition to ceasing the use and reliance on fossil fuels, deforestation urgently needs to be stopped, and restoration of forests must drastically increase. Trees take in carbon dioxide during photosynthesis which counteracts global warming. The more trees we have on the planet, the more carbon dioxide that is absorbed by them. And the more trees are cut down, the more carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are released into the atmosphere, in addition to the habitats being destroyed for billions of animals globally.

Where there is demand, there is supply. Ways the public can get involved in reducing energy demand is by buying organically and locally produced foods and products; and using more public transportation (where demand for public transportation increases, so does frequency and quality) and active forms of travel such as cycling, walking and running. Also ensure all electricity is turned off when not in use, and reduce, reuse and recycle as much as possible. These actions cumulatively help reduce energy demands, particularly for fossil fuels.

Currently, the top countries of greenhouse gas emitters in order are China, the US, Russia, India, and Japan. However, the per capita emissions of the US is 5 times higher than China and 20 times higher than India.

Another solution is artificially changing nesting temperatures using scientifically-based interventions. While this is not a direct solution to climate change, this approach is essential to support the survival of sea turtle populations in the meantime. Increasing shade cover on beaches using marquees or by planting vegetation could improve sex ratios. A 2018 study by Esteban and colleagues in St. Eustatius in the northeast Caribbean found that palm leaves was the most effective shading material, and concluded that relocation and shading could shift ratios from current 97–100% females to 60–90% females. At Junquillal Beach, Costa Rica, on the Pacific coast, where it is often too hot for eggs to hatch at all, scientists have begun moving eggs to nurseries, which are essentially holes dug to a certain depth on cooler areas of the beach. When the hatchlings emerge, rangers chaperone them from the nest to the water, protecting them against human and animal predators alike.

In addition, establishing environmental restoration and protection measures will help save many species and their habitats. For example, coral regeneration schemes restore damaged and endangered reef ecosystems, such as the Baa Atoll in the Maldives. Scientists and volunteers alike collect coral fragments from local reefs to be raised in nurseries until maturity, and later plant or restore them at reef sites. These schemes have been proven to be an effective method for successfully restoring thriving reef systems around the world.

The rapid loss of species we are seeing today is estimated by experts to be between 1,000 and 10,000 times higher than the natural extinction rate. These experts calculate that between 0.01 and 0.1% of all species become extinct each year – that means between 200 and 2,000 extinctions occur every year (assuming that there are around 2 million different species on our planet). However, the good news is that the energy and resources devoted to saving species often work, and is evident with the recent increase in turtle numbers around the world, despite the situation remaining volatile.

Education about the effects burning fossil fuels and deforestation have on climate change, and its subsequent impacts on sea turtles, other life on Earth and their ecosystems, and the natural environment is essential to ensuring people reduce and change their consumption habits and consciously buy products that are energy efficient (e.g. Energy-Star qualified, energy efficient fluorescent bulbs) an not derived from fossil fuels or as a result of deforestation (products derived from illegally harvested trees or illegally cleared land).

The amount of energy we use is also highly dependent on human population. As human population eventually declines, the demand for energy decreases and can be more easily managed, and will be much easier and quicker to switch from fossil fuels to 100% renewable energy.

Stricter environmental regulations and environmental conservation education is necessary to help mitigate climate change.

Summary

- Cessation of offshore drilling and extraction of fossil fuels must be imminent.

- An increase in renewable energy leads to the creation of jobs in energy conservation and renewables which will help swiftly shift the economy away from fossil fuels.

- Cessation of deforestation must happen, and the restoration of forests must drastically increase.

- Buy organically and locally produced foods and products.

- Use more public transportation (where demand for public transportation increases, so does frequency and quality) and active forms of travel such as cycling, walking and running.

- Ensure all electricity is turned off when not in use.

- Reduce, reuse and recycle as much as possible.

- Artificially changing nesting temperatures using scientifically-based interventions to improve sex ratios, such as increasing shade cover on nesting beaches using marquees or by planting vegetation, or moving the eggs to nurseries in cooler areas of the beach.

- Establishing environmental restoration and protection measures and schemes for scientists and volunteers alike, for example, coral regeneration schemes.

- Educate the public about the effects burning fossil fuels and deforestation have on climate change, and its subsequent impacts on sea turtles, other life on Earth and their ecosystems, and the natural environment.

- As human population eventually declines, the demand for energy decreases and can be more easily managed, and will be much easier and quicker to switch from fossil fuels to 100% renewable energy.

- Stricter environmental regulations and environmental conservation education is necessary to help mitigate climate change.

References

Butt, N., Whiting, S. & Dethmers, K. Identifying Future Sea Turtle Conservation Areas Under Climate Change. Biological Conservation 204, 189-196 (2016).

CMS: Loggerhead Turtles & Climate Change

Esteban, N., Laloë, J. O., Kiggen, F. S. P. L. et al. Optimism for Mitigation of Climate Warming Impacts for Sea Turtles Through Nest Shading and Relocation. Nature Scientific Reports 8(17625) (2018).

Fuentes, M. M. P. B., Allstadt, A. J., Ceriani, S. A. et al. Potential Adaptability of Marine Turtles to Climate Change May be Hindered by Coastal Development in the USA. Regional Environmental Change 20(3) (2020).

Fuentes, M. & Cinner, J. Using Expert Opinion to Prioritize Impacts of Climate Change on Sea Turtles’ Nesting Grounds. Journal of Environmental Management 91(12), 2511-2518 (2010).

Hays, G. C. Ocean Currents and Marine Life. Current Biology 27(11), R470-R473 (2017).

Jensen, M. P., Allen, C. D., Eguchi, T. et al. Environmental Warming and Feminization of One of the Largest Sea Turtle Populations in the World. Current Biology 28, 154-159 (2018).

LiveScience: Acid Rain – Causes, Effects and Solutions

Luschi, P., Hays, G. C. & Papi, F. A Review of Long-Distance Movements by Marine Turtles, and the Possible Role of Ocean Currents. Oikos 103(2), 293-302 (2003).

MEDASSET: Climate Change

Mortimer, T. Acid Rain: The Effects. (California Polytechnic State University, 2009).

National Geographic: Ocean Currents and Climate

Natural History Museum: How Does Climate Change Affect the Ocean?

Natural History Museum: How Does Ocean Acidification Affect Marine Life?

NASA Climate Kids: How Does Climate Change Affect the Ocean?

New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services: Acid Rain

Oceana: Sea Turtles and Climate Change

Perez, E. A., Marco, A., Martins, S. & Hawkes, L. Is this what a Climate Change-Resilient Population of Marine Turtles Looks Like? Biological Conservation 193, 124-132 (2016).

Science: Sea Turtles Ride the Waves

Sea Turtle Conservancy: Double Trouble – Climate Change and Ocean Acidification

Sea Turtle Conservancy: Threats from Climate Change

Sea Turtle Preservation Society: Hurricanes and Sea Turtles

See Turtles: Global Warming and Sea Turtles

Sustainable Travel International: Sunscreen is Damaging Our Coral Reefs – How Can We Protect Them AND Our Skin?

SWOT: What does Climate Change Mean for Sea Turtles?

Tibbetts, J. Bleached, But Not By The Sun: Sunscreen Linked To Coral Damage. Environmental Health Perspectives 116(4), 173 (2008).

University of Miami Shark Research: Climate Change Effects on Sea Turtles

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution: The Oceans Feel Impacts from Acid Rain

WWF: Sea Turtles and Climate Change

Image Source: Figure 1. Global temperature change over the last 2000 years – Consistent Multi-Decadal Variability in Global Temperature Reconstructions and Simulations over the Common Era, 2019

Image Source: Figure 2. Global temperature change since the end of the Industrial Revolution – Global Warming of 1.5°C: An IPCC Special Report (Chapter 1), 2018